By Lena Kotler-Wallace

I was born a Good Girl. In sweet, pinafored dresses, hair tied neatly with a ribbon, hanging down straight and shining to the small of my back – because I brushed it every night 100 times like someone from somewhere once said to. I was precocious, but not in that obnoxious way, so as not to challenge the adults around me. Like a good Southern child my “pleases and thank yous” were always followed by a “ma’am” or “sir” strung out with a charming drawl that hinted at more of the kind of genteel South, sweet teas sipped on porches, than it did of the banjo-playing, cousin-screwing hillbilly variety.

I was a Good Girl, and good girls got praise. They got love. They got fathers who paraded them proudly in front of friends to recite their multiplication tables or mothers who hugged them tightly as they stood tall, a perfect doll-like trophy. Good girls got parents who told stories hinting not so subtly that their daughter was not just pretty but SMART.

Good girls did not get the terrifying father who slammed doors while their hand was still in the frame, or who left them sprawled out on the floor, his handprint welling upon their cheek when they corrected his math.

Good girls did not get that glaring look from their mothers. The ones that let them know that with a single childlike misstep such as forgetting to clean their room or making a B on that quiz, they could be too much for the Good Girl persona to bear.

That look and those words inevitably let me know I had suddenly slipped from being The Good Girl to (capital T) Trouble.

I learned very early on that I did not want to be Trouble.

As a child growing up in one of those houses that the neighborhood kids were told they couldn’t play at as their parents pretended they couldn’t hear the horror show going on behind closed curtains, I learned bad things happened because you deserved them, and, if only I had been a Good Girl, then daddy wouldn’t hit, and mommy wouldn’t say those mean things that honestly left wounds much deeper than any punch my dad could throw.

I avoided trouble like it was my sacred mission. The Holy Grail of Good, however, proved to be a difficult thing to achieve. Turns out living in a fear-filled, abusive household tends to give a person some mental health issues, and things like depression and bipolar disorder are not something that Good Girls contract.

I soon learned that Good Girls also only come in sizes like thin or straight. They are only that 1990s kind of liberal that’s really just a Republican in a blue power suit. They are not radicalized. They are not queer. They don’t fucking curse. They are not any of those things that can’t politely be put on the family Christmas card.

Good girls are silent trophies you put up on a shelf. They aren’t me.

Now, staring down the barrel of 35, those people who taught me to fear trouble are all dead and buried. The monsters in the dark are gone, and I can finally face the truth that chasing the phantom of the Good Girl won’t protect me. That actually it never did.

And maybe that’s okay.

Being silent. Being good. Well, it’s no longer an option.

Because life can’t be lived in perfection. The very act of living and existing in our world means that at one point or another you will be too much for someone, not enough for someone else.

You will be too smart.

You will not be in the right body.

You will be tired, and you will say the wrong thing.

You won’t be tired at all, and you will still say the wrong thing.

No matter what you do. No matter how carefully you try to pass in our fucked-up world, you will somehow not fit in that straight cis/het mold of the Good. The day will come when it is your turn to be trouble, and that is not something we should be scared of.

We can’t.

I can’t.

Not just because I deserve that kind of unconditional existence. I do. But so do those three kids who now call me Mom, who are looking to me for love.

And I’m going to love the ever-living shit out of them. I will love them when they bring home A’s, and I will love them when they forget to do their homework entirely. I will love them when their rooms look like a hazmat team is needed, and I will love them through all of the messiness of life. They will know that they are safe and celebrated, and, no matter how much trouble they may be, they will know this is not a home that worships at the altar of The Good Girl.

This is a house that makes trouble.

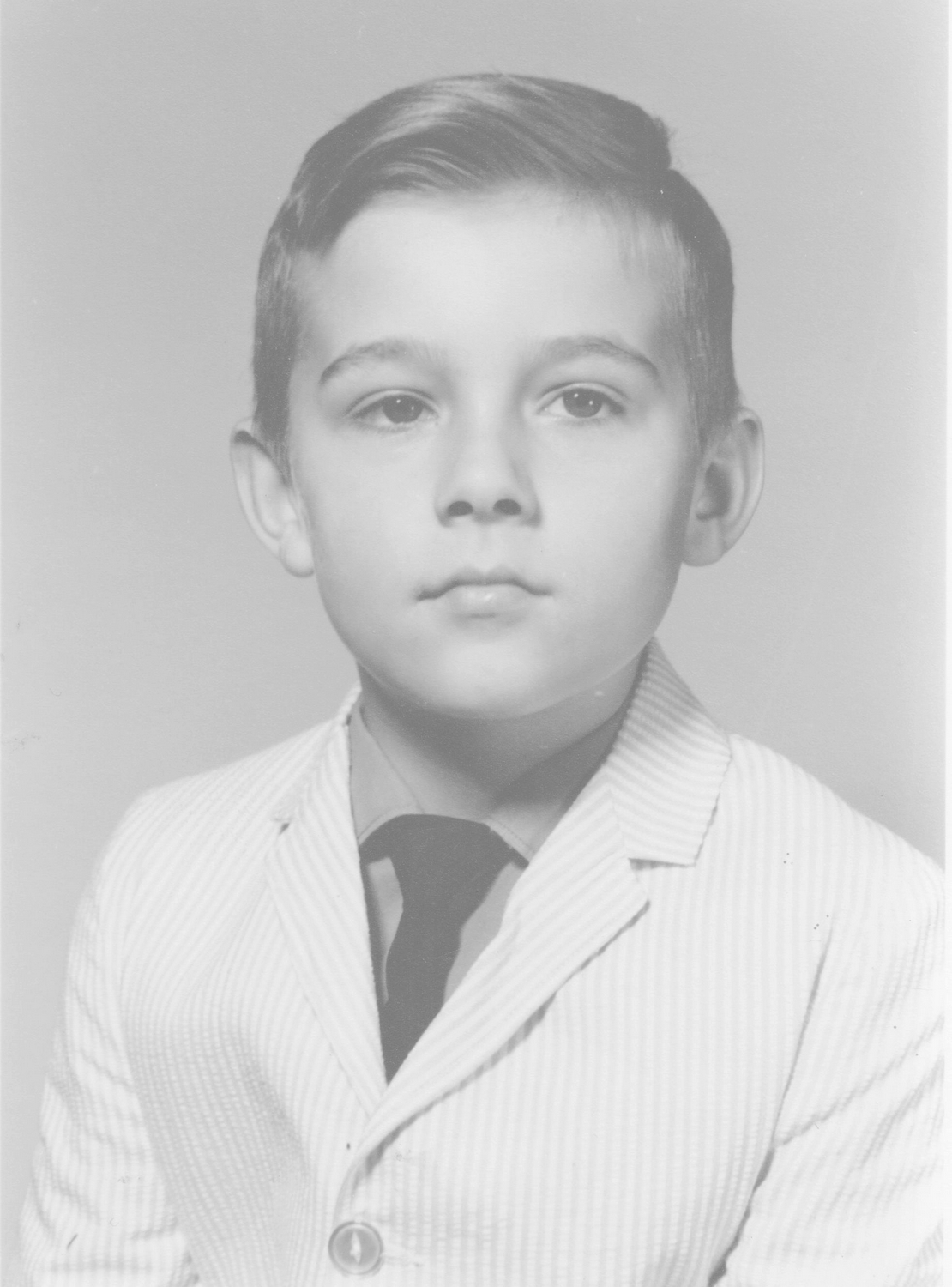

Here’s me in 1961, the sad first-grader from Illinois, arrived with his grandparents for a week with Virginia mountain kin. He shuffles from the gas station, peels the wrap off a Popsicle. Cuts across the outfield, past the tomboy who fist-smacks her mitt, waiting for the play.

Here’s me in 1961, the sad first-grader from Illinois, arrived with his grandparents for a week with Virginia mountain kin. He shuffles from the gas station, peels the wrap off a Popsicle. Cuts across the outfield, past the tomboy who fist-smacks her mitt, waiting for the play.