By E.M. Yeagley

On a good day, you and your mother wait on Cora’s doormat while the cast recording of South Pacific seeps through her wall. She answers the door looking radiant, with the front of her hair done up in tight pin curls, a bright red smear of lipstick on her dentures.

She’s still young–young for a grandmother, certainly, and she looks good. She dyes her hair red or black, depending on drugstore sale prices. Cora has tiny tits and a huge ass, but taken all together, it works.

When things are calm, her apartment smells of coffee and lemon Pledge, and she gamely pretends to be offended when your mother screams in mock terror at the velvet Jesus above her toilet. Cora has a sixth sense about kids–she’s hidden shoe boxes painted to look like treasure chests throughout the apartment. You make a beeline for one, parsing through the costume jewelry, the telescopic cigarette holder, the homemade Play-Doh, the seahorse-shaped cocktail stirrers.

She and your mother play Gin Rummy at the kitchen table. After a couple of hands, Cora starts with the funny stories. The punch lines often involve her lobbing a real zinger at an unsuspecting stranger:

“—in the checkout line! I said, ‘Lady, if you ram me in the ass with that cart one more time—’”

“And I told him, ‘Phil—it is Phil, right? Try wishing in one hand and shitting in the other, and let me know which Phils up first. Ha!”

Stories are her specialty. Visiting, she calls it, although conversations with Cora are generally one-sided. The stories are funny, and you’ll laugh, but uneasily. You were there the time she chased down a guy for braking too quickly. “Are you out of your fucking mind?” she yelled against his rolled-up window, squeezing your hand hard enough to bruise. “I had my granddaughter in the car! I’m placing you under citizen’s arrest!”

When Cora finally comes up for air, your mother asks about her Lithium, and she demurs. When pressed, she tells your mother to back off, that she feels great.

In Cora’s bathroom, your mother finds a mostly-full prescription bottle at the bottom of the wastebasket, beneath a wad of lipstick-blotted toilet paper. Post-its line the wall next to the mirror–project ideas, song lyrics, Bible verse, grocery lists.

There are telltale signs of hypersexuality, too: a cologne-reeking, pit-stained undershirt slumps over the toilet tank, beneath the velvet Jesus. Your mother imagines its anonymous owner taking a leak eye-to-eye with our savior. She remembers the time she overheard one of Cora’s boyfriends saying that crazy chicks make better lays, and prays that, whoever he was, he brought condoms and was kind.

In the kitchen, there’s a confrontation. Cora doesn’t need the pills anymore. Her own daughter doesn’t trust her. Everyone’s full of shit. Everyone’s a piece of shit. It’s time to go home. Your mother takes a deep breath as the door closes behind you.

Once upon a time, Cora was married to her high school sweetheart, your grandfather. He was a police officer and, later, a TV weatherman. When you were still an infant, your mother took you to the television station to meet him. “Just let me hold her once,” he pleaded. “Just five minutes.”

Even in front of all those cameras and people, she handed you over reluctantly, stood close enough to snatch you back and run. You peed down his shirt; he covered it up with a jacket and delivered the weather like everything was normal. You never saw him again.

Because it seems so unreal, you sometimes have to remind yourself that long before you were born, when your mother and aunt and uncles were still children, your grandfather exploited Cora’s mental illness in order to conceal his own.

Late one night, Cora woke up and walked out to the yard. Your grandfather stood in the dark next to his cruiser, eyes wide and wild. In the back seat lay a bicycle and two small sets of clothing, two small sets of underwear.

“I was teaching them how to swim,” he told her. “If anyone asks, that’s what you say.”

And that is how she found out what he was. What he’d done. That’s how she figured out that he’d been doing the same to their children, his sister’s children, and now neighborhood children. When Cora tried to leave with your mother and her siblings, he called his buddies at the police station, and then the hospital.

“My wife is having another episode,” he said. “We’ve been through this before. She a needs a few months of rest and quiet; she responds well to electroconvulsive treatments.”

At the house, they looked at her–howling, spitting, throwing punches–and then at him–calm, concerned, controlled. A fellow officer. A man. Your mother and her siblings were too terrified to speak. Cora didn’t stand a chance.

He signed the forms; they pried her lips apart and shoved a bit between her teeth, ignored her when she swore to them that she saw this thing and knew it to be true, and worse, and worse, and please, I need to save my children, please. Strapped to that table, with 460 volts rattling her skull, she alone knew the real reason he sent her there, and if she wasn’t crazy before, well.

From time to time, you think about this, and your stomach will twist up and go sour. When Cora is being especially combative, you try to put things in perspective:

If she wants to talk nonstop and listen to show tunes and eat junk food all day without getting shit from anyone, why not? If she gets satisfaction from causing scenes in the supermarket checkout line, can you really blame her? So what if she passes out and burns the house down. Has she not earned it?

Later, you learn that it continued for years. That your grandfather’s second wife was complicit. His own mother was complicit. You learn that his mother did the same to him and his sister. You collect pieces of the story, each more abhorrent than the last, and file them away. You feel powerless, as Cora must have.

When your grandfather enters into hospice, half of Cora’s children go to watch him die. Once he’s dead, she refuses to collect his social security money.

***

Now she takes you to Chuck E. Cheese and shows you how to spot the tables with abandoned pizza.

Now she has a new boyfriend who used to be in the Black Panthers. She’s permed her red hair into an embarrassing White Lady Afro and wears a dashiki out in public.

Now she’s up all night with you building pillow forts, distracting you from an ear infection. She lets you eat two full rows of Oreos.

Now she insists on handing out condoms from a plastic Jack-O-Lantern outside the 7-Eleven.

***

You’re almost grown now; your life has been better than you realize. Cora lives with you, and today she’s talking an awful lot. If she in any way notices the tightening at your jawline or the apprehension in your eyes, she won’t let on. You run through the mental checklist of warning signs, ultimately concluding that this is just Cora being extra Cora-like. It isn’t always so easy to tell—she’s enthusiastic by nature. She speaks loudly and irreverently regardless of her mental state. Life has taught her that the most important thing is to be heard.

Not for the first time, you’ll marvel at how much smarter and funnier and weirder she is than other people’s grandmothers. You once found among her stuff a high school report card that sums things up nicely: Cora is unusually bright, it said, but prone to outbursts and difficult to control.

On a manic day, Cora begins early, long before the sun rises. She hasn’t slept in a while and has more energy than she knows what to do with. She wants action, excitement, noise, people—above all else, she craves conversation, but no one is awake. She takes a shower to pass the time. The night air filtering through the open window feels incredible against her skin. She throws open the shades and decides against getting dressed, although she will put on one, two, three coats of lipstick. Sometimes she’ll stay naked all day; you learn not to bring friends home after school when she’s high.

She makes a pot of coffee, drops a Danny Kaye record on the ancient Zenith, and scrubs down the kitchen.

Manic-Depressive Pictures presents:

Hello, Fresno, Goodbye!

Produced by R. U. Manic

And directed by Depressive…

By the time the record ends, she cannot wait any longer and heads for the phone. If they don’t answer, she calls back. If they do answer, she calls back.

On a manic day, Cora serves you a box cake buried beneath three inches of icing–Happy Birthday in her vining cursive, three months early. Egg salad straight out of a mixing bowl. On the first bite, you crunch down on shell. No time to peel the eggs.

Perhaps she’s bought nothing but bananas for weeks. There are green ones piled on the counter tops. Dense, bruised bunches in brown paper bags abandoned just inside the door. Bananas fill the freezer, blackening against the scummy drifts of frozen condensation. The house reeks. Fruit flies congest the air in ashy clumps; layers of their tiny, dried out husks collect in the windowsills, in the stove’s drip pans, behind the sofa. Walking through the kitchen is much like witnessing the final hours of Pompeii.

Your mother reaches her limit, finally chucking them all in the dumpster. Cora is livid. “How dare you.”

The years pass. The rest of Cora’s body catches up with her big ass. She gets meaner, as old people often do. Her highs aren’t as high–she’s irritable and obsessive more often than euphoric–but the lows, the lows are abyssal.

On a bad day, you find Cora sitting on the sofa in the dark, smoking pack after pack of Marlboro Lights. Her speech slurs; she may scream or sob or press the heel of her hand against her temple when you ask if she’s okay.

On a bad day, Cora might tell you that she’s ashamed of you, that you make her sick, that your mother is useless, that you are the reason your mother never finished college. She finds the chinks in your armor and digs in. Once you are exposed, she becomes glass shards and serrated edges.

***

Now she’s taken too many downers, tripped and busted her forehead open; you hold her hand as the surgeon sews her back up. “You should have left me there,” she says. “You should have left me.”

Now she’s sitting on the floor with a pair of scissors, cutting your mother’s work uniforms into tiny pieces.

Now she thinks she’s psychic; the Virgin Mary talks to her, tells her that all of her children forgive her.

Now she’s in the hospital again, and although it’s the right thing to do, your mother hates herself for sending her there.

***

Once that well of dopamine has run dry, foul memories take Cora hostage. On a terrible day, she won’t open the door, no matter how long or loud you knock. If you are especially brave or especially unnerved, you might force your way in.

It could be that she’s in bed, stretched into a shapeless old sack from too many days without rest. Or perhaps she’s so overwhelmed by the aggregate of her life’s tragedies that her legs cannot bear her weight. Or she’s finally given up, the unthinkable, the unspeakable. That time may come, but for now, Cora presses ever on.

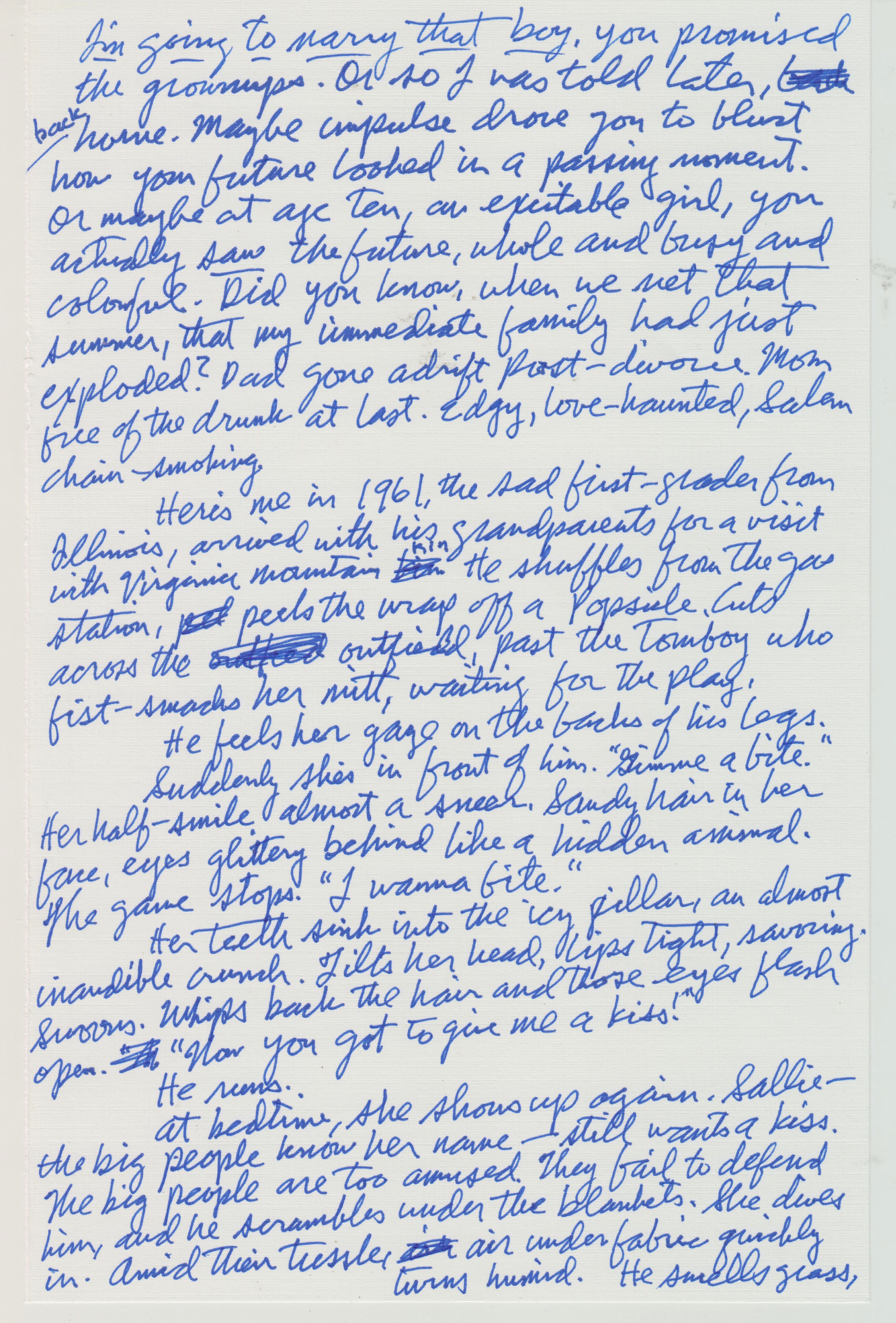

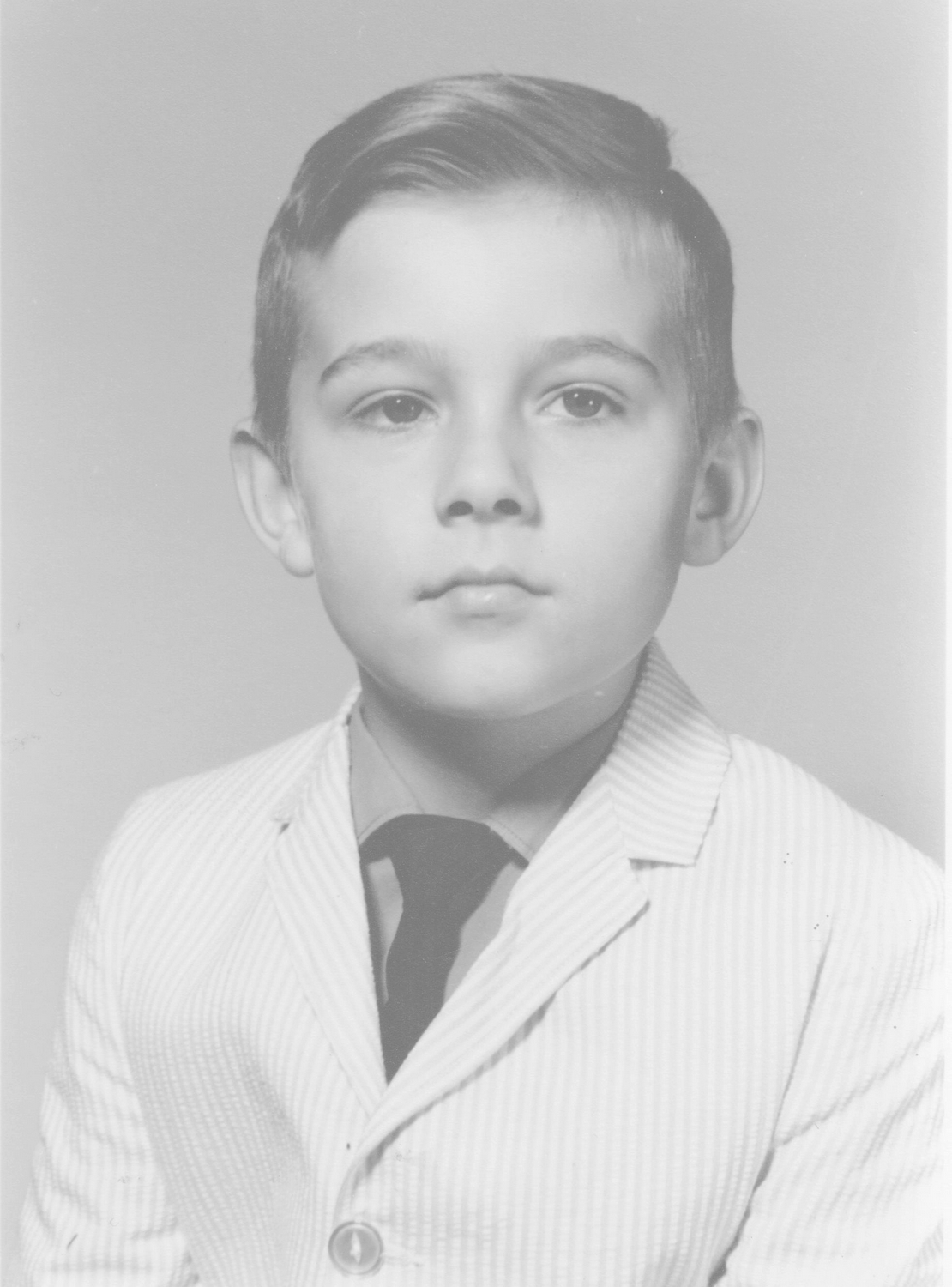

Here’s me in 1961, the sad first-grader from Illinois, arrived with his grandparents for a week with Virginia mountain kin. He shuffles from the gas station, peels the wrap off a Popsicle. Cuts across the outfield, past the tomboy who fist-smacks her mitt, waiting for the play.

Here’s me in 1961, the sad first-grader from Illinois, arrived with his grandparents for a week with Virginia mountain kin. He shuffles from the gas station, peels the wrap off a Popsicle. Cuts across the outfield, past the tomboy who fist-smacks her mitt, waiting for the play.